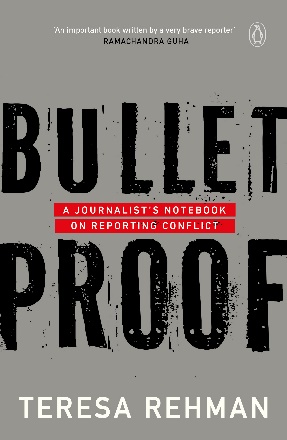

In Bullet Proof – A journalist’s notebook on reporting conflict by Teresa Rehman, the journalist lays bare her own vulnerability as a reporter focusing on conflict areas.

The book recounts her experiences as a reporter working in a conflict zone in North East India. It highlights the human side of conflicts, going beyond mere facts and delving into emotional impact of conflicts.

She also chronicles the deep and far reaching impact of conflicts on common people, especially women and children. Very often, in desensitized TV reportages we fail to see a whole picture, and we definitely fail to see the human picture!

Bookedforlife in conversation with author Teresa Rehman……

You have very honestly talked about the emotional and psychological impact that your work has had on you, and you have been open about seeking professional help. What is your advice to reporters (and other professionals) who often unknowingly internalize emotional impact caused due to their professions?

Yes, this book is also a story about my evolution as a journalist covering conflict. Reporting from a conflict zone has a fear factor that is real. In order to report from a conflict-zone, we journalists tend to become ‘bulletproof’ ourselves — internalizing emotional trauma without realizing its impact on our psyche. And the physical risks are not to be discounted. And, reporting from one of the most under-reported regions of the world i.e. Northeast India, with practically no support system for journalists is like walking on a tightrope. We journalists never seem to talk about our vulnerabilities and apprehensions. I had to muster courage to visit a psychiatrist for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

But it took me years to openly talk and write about it. It was much later that I came to know of courses like Hostile Environment and First Aid Training (HEFAT) organised by organisations like the International Women’s Media Foundation (IWMF) that trains journalists from various backgrounds, mediums, and levels of experience. A decade ago, I was ignorant of the fact that I could get some training in areas like emergency first aid, digital security, civil unrest/demonstrations, situational awareness, reaction under gunfire etc.

My advice to reporters (and other professionals) is that your personal health (both physical and mental) is equally important. And with the cyber boom, there is enough information available online on the various kind of support services available. There is no shame in talking about your little frailties and fears and if necessary, seek professional help.

As a reporter you spent days on the ground and in the interiors of conflict-ridden areas, in the midst of danger. At the same time, you are a mother of two girls, often taking them on assignments with you! How did you balance these two vastly different facets of your life?

I was juggling too many roles. Not just being a mother to two daughters, I was also taking care of my terminally ill mother. There were occasions when I took my daughters with me on my assignments. I made them sit near me. They were part of my accessories along with my notepad and pen! And I was also working full-time when I was expecting my second child. I never thought motherhood was a burden. Being the first journalist in the family, I had nobody to guide me either. Since, I was passionate about my work, I tried to multi-task. Many a times I worked on the kitchen table while cooking dinner for the family. And my children learnt to cope with their busy, hardworking and absent-minded mother!

You talk about the rehabilitation of women in conflict areas, and of economic empowerment that is brought about by certain organisations working with them. How important are these measures to make positive changes in the scenario?

I always believed in going beyond mere statistics and the very masculine reportage of conflict, about arms, artillery and dead bodies. For me the real stories were the stories beyond the conflict – of women and children. In any kind of conflict situation, they are the most marginalised and the worst affected. And any kind of rehabilitation measures for them is like a silver lining. I feel good reporting about such subtle changes that bring about happiness in people who have seen decades of violent conflict. For me, reporting this kind of positive stories is like a catharsis and a hope for peace.

You have written about the hospitality that you received on your visits to militant camps. At the same time, you have also chronicled the heart wrenching impact of conflicts on common people. On the other hand, they are viewed differently by the government. From your experience, what role can media play in this scenario?

The publicity wing of any militant organisation is one of their most important wings. They understand the power of the media and probably that is why they had been hospitable to me. And being a journalist in a conflict zone is like walking on a tightrope as a journalist can incur the wrath of both the state and the non-state actors. It is the job of a journalist to maintain a precarious balance and report objectively and if possible, look beyond the mere statistics and press releases. The job of a journalist is to get the real stories of men, women and children trapped in such a situation.

How do you remain non-judgemental in this field of work, where what is right and wrong is often so complex to decide for yourself!

I have learnt to understand the nuances of the social milieu and the conditions that perpetuate the conflict. I avoid being judgmental and just report and state facts. I don’t think it is the journalist’s job to decide what is right or what is wrong. It is the journalist’s job to sensitively and sensibly tell the human stories in a very complex situation.

It is a strange coincidence that as we write about your book, the issue of the inadequacies of the NRC list has flamed many segments of people. What is your take on this?

We all want a free and fair NRC in Assam. However, it should not evolve into a humanitarian crisis. We all believe in the Constitution of India and I am sure everyone will get a fair opportunity to prove their citizenship irrespective of caste, creed and religion. Though a tedious process, we have all been cooperating with the authorities. And, we are all hoping for a judicious and humane outcome of the whole exercise.

What do you want readers to take away from Bulletproof?

Bulletproof is the story of a ‘female’ journalist reporting from a conflict zone. It is not just my story. It is the story of many journalists like me who are constantly flirting with danger and reporting from regions that are out of the radar of the so-called ‘national’ media and considered inaccessible, unsafe and unimportant.

Bullet Proof – A journalist’s notebook on reporting conflict is indeed not only very interesting to read, but highly inspirational! It is a great guide for reporters, but on a deeper level I believe it is inspirational for working women, for journalists working in conflict situations as well as mothers across society! It really talks to all these diverse groups at the same time! There are two aspects to the book- first, there is a reporter’s diary, which provides behind-the-scenes look at a reporter reporting for a zone of conflict. Being a woman, and a mother adds another unique dimension to this. The other aspect is the personal emotional journey of a human being, who happens to be a woman and a mother, who tries to look at her work with new eyes.

Interested in reading books written by Indian women journalists? Click here.