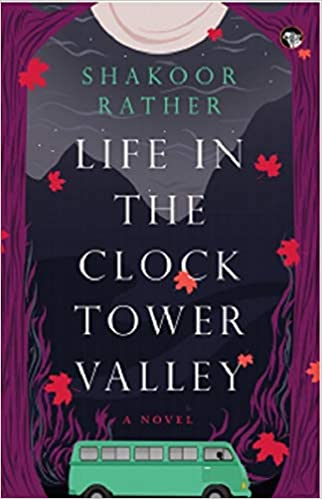

There is the Kashmir that we know about through news coverage and popular media. And then, there is one that finds expression in voices of people who call it home. Life in the Clock Tower Valley by Shakoor Rather (Speaking Tiger) is a novel that weaves in poignant stories of Kashmir in a single layered narrative. The author is a Kashmiri journalist who has not only written about Kashmir extensively but also grown up here. Thus, a rare sensitive perspective pervades the novel.

We follow young Samar’s budding love for Rabiya, a girl who studies in the same university. Parallel to this love story is the story of Sheikh Mubarak, Samar’s neighbour and a famed metal craftsman. He is married to Naziya, but the arrival of Rosaline, a tourist, stirs something within him. Rosaline is an outsider whose soul seeks to be healed in the beauty of Kashmir. The other characters in the novel, that is, Sana, Mubarak’s five-year-old daughter and Pitonji, the neighbourhood simpleton also provide a novel perspective on life in the valley.

As a reader one understands how local people try and make life as normal as they can, despite the political strife’s that mark the land. On one hand, there is a nostalgia of the Kashmir that was. The references to its glorious past make us yearn for that fragile mystical beauty that marked the land. As readers we see how ‘development’ not done right has impacted the land at present. In the first chapter there is a reference to the government having had an original canal filled up, and paving way for disastrous ecological consequences. There are also echoes of old arts dying out. For example, no one makes houseboats any more, in the manner they used to. In this context we could be talking about any small town that has been expanding and developing over time.

But then, this is Kashmir. And there is a difference. There are subtle reminders that all’s not well. As one reads the book we can sense how this pervades the life of the common people- army vehicles who would check regular busses plying to and fro for instance. There is a sense of the desolation and the suffering of the common man in wake of the frequent curfews that are a part of the valley life. Whether it is Mubarak‘s plight on not being able to save his cow due to lack of medical supplies in the curfew; or the plight of lovers who need to snatch few moments of freedom as curfews are lifted, just to see each other, one feels deeply for the residents. It is disheartening to see the image of Mubarak and his men playing carom outside his metal workshop, in the hope that the curfew may be lifted and they could snatch in a few hours of work! But perhaps what hits the most is the fact that people have to ‘prove’ themselves. “He disliked the idea of having to prove his identity every time, in his own land-his land of chinar trees and snowcapped mountains,” it is said of Mubarak.

And while the themes are universal, the glorious cultural legacy of Kashmir is at play all through the book. The taste of Kashmir in the descriptions of the delightful cuisine- the hot saffron-flavoured Kahwa, the beakir khaen (a fluffy bread); the small tea shops that turn into spaces of exchange of views and ideas; the impact of sudden and frequent lockdowns on life in the valley; all these aspects bring out Kashmir authentically.

The novel resonates with the reader at a universal level. It leaves one with a bittersweet feeling …but also a feeling of empathy and understanding towards those who call it home.

for more fictional explorations on Kashmir click here.